Perfumeria Brasil Is Owned by Japanese Brazilian Family

| Nipo-brasileiros | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Total population | |

| c. 2 meg Brazilians of Japanese descent (2019)[1] | |

| Regions with meaning populations | |

| Japan: 208,857 (2019) Japanese Brazilians in Japan [ii] 0.two% of Japan'southward population | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese • Japanese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Roman Catholicism[3] Minority: Buddhism and Shintoism[4] Japanese new religions Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Japanese, other nikkei groups (mainly those from Latin America and Japanese Americans), Latin Americans in Japan |

Japanese Brazilians (Japanese: 日系ブラジル人, Hepburn: Nikkei Burajiru-jin , Portuguese: Nipo-brasileiros, [ˌnipobɾaziˈlejɾus]) are Brazilian citizens who are nationals or naturals of Japanese beginnings or Japanese immigrants living in Brazil or Japanese people of Brazilian ancestry.[5]

The first group of Japanese immigrants arrived in Brazil in 1908.[6] Brazil is home to the largest Japanese population outside Japan. Since the 1980s, a return migration has emerged of Japanese Brazilians to Nihon.[vii] More recently, a tendency of interracial marriage has taken concord among Brazilians of Japanese descent, with the racial intermarriage rate approximated at 50% and increasing.[8]

History [edit]

Background [edit]

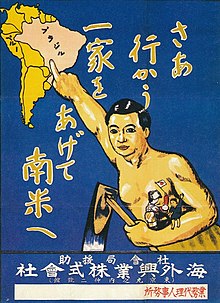

A poster used in Nippon to attract immigrants to Brazil and Peru. It reads: "Allow'south go to Due south America (Brazil highlighted) with your unabridged family."

Betwixt the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, java was the main export production of Brazil. At kickoff, Brazilian farmers used African slave labour in the coffee plantations, but in 1850, the slave merchandise was abolished in Brazil. To solve the labour shortage, the Brazilian elite decided to attract European immigrants to work on the coffee plantations. This was also consistent with the authorities's button towards "whitening" the land. The promise was that through procreation the large African and Native American groups would be eliminated or reduced.[ix] The regime and farmers offered to pay European immigrants' passage. The programme encouraged millions of Europeans, about of them Italians,[10] to migrate to Brazil. However, once in Brazil, the immigrants received very depression salaries and worked in poor atmospheric condition, including long working hours and frequent ill-treatment past their bosses. Considering of this, in 1902, Italian republic enacted Decree Prinetti, prohibiting subsidized emigration to Brazil.[11]

The end of feudalism in Nippon generated great poverty in the rural population, and then many Japanese began to emigrate in search of meliorate living conditions. By the 1930s, Japanese industrialisation had significantly boosted the population. Yet, prospects for Japanese people to migrate to other countries were limited. The U.s. had banned not-white clearing from some parts of the world[12] on the basis that they would non integrate into lodge; this Exclusion Clause, of the 1924 Immigration Human action, specifically targeted the Japanese. At the same time in Australia, the White Australia Policy prevented the immigration of non-whites to Australia.

First immigrants [edit]

In 1907, the Brazilian and the Japanese governments signed a treaty permitting Japanese migration to Brazil. This was due in part to the decrease in the Italian clearing to Brazil and a new labour shortage on the coffee plantations.[13] Also, Japanese immigration to the United States had been barred past the Gentlemen'southward Agreement of 1907.[14] The showtime Japanese immigrants (790 people – by and large farmers) came to Brazil in 1908 on the Kasato Maru. About half of these immigrants came from southern Okinawa.[15] They travelled from the Japanese port of Kobe via the Cape of Proficient Hope in Due south Africa.[16] Many of them became owners of coffee plantations.[17]

In the first seven years, iii,434 more Japanese families (14,983 people) arrived. The offset of World War I in 1914 started a boom in Japanese migration to Brazil; such that between 1917 and 1940 over 164,000 Japanese came to Brazil, 75% of them going to São Paulo, where almost of the coffee plantations were located.[xviii]

| Years | Population |

|---|---|

| 1906–1910 | nine,000 |

| 1911–1915 | 13,371 |

| 1916–1920 | 13,576 |

| 1921–1925 | 11,350 |

| 1926–1930 | 59,564 |

| 1931–1935 | 72,661 |

| 1936–1941 | 16,750 |

| 1952–1955 | 7,715 |

| 1956–1960 | 29,727 |

| 1961–1965 | 9,488 |

| 1966–1970 | 2,753 |

| 1971–1975 | 1,992 |

| 1976–1980 | i,352 |

| 1981–1985 | 411 |

| 1986–1990 | 171 |

| 1991–1993 | 48 |

| Total | 242,643 |

New life in Brazil [edit]

The vast majority of Japanese immigrants intended to work a few years in Brazil, make some money, and get habitation. However, "getting rich quick" was a dream that was almost impossible to achieve. This was exacerbated by the fact that it was obligatory for Japanese immigrants to Brazil prior to the 2d Globe War to immigrate in familial units.[21] Because multiple persons necessitated monetary support in these familial units, Japanese immigrants found it nearly incommunicable to return home to Nihon even years after emigrating to Brazil.[21] The immigrants were paid a very depression salary and worked long hours of exhausting piece of work. Also, everything that the immigrants consumed had to be purchased from the landowner (see truck system). Soon, their debts became very pregnant.[18]

The land owners in Brazil still had a slavery mentality. Immigrants, although employees, had to face up the rigidity and lack of labour laws. Indebted and subjected to hours of exhaustive work, often suffering physical violence, the immigrants saw the leak [ clarification needed ] as an alternative to escape the situation. Suicide, yonige (to escape at night), and strikes were some of the attitudes taken by many Japanese because of the exploitation on coffee farms.[22]

The barrier of language, faith, dietary habits, clothing, lifestyles and differences in climate entailed a civilisation shock. Many immigrants tried to return to Japan but were prevented by Brazilian farmers, who required them to comply with the contract and work with the coffee.[ commendation needed ] Even when they were free of their contractual obligations on Brazil'southward java plantations, it was often impossible for immigrants to return dwelling due to their meager earnings.[21] Many Japanese immigrants purchased land in rural Brazil instead, having been forced to invest what little capital they had into state in order to someday make enough to return to Japan. Every bit independent farmers, Japanese immigrants formed communities that were ethnically-isolated from the residual of Brazilian order. The immigrants who settled and formed these communities referred to themselves equally shokumin and their settlements equally shokuminchi.[21]

On 1 August 1908, The New York Times remarked that relations between Brazil and Japan at the time were "not extremely cordial", because of "the mental attitude of Brazil toward the clearing of Japanese labourers."[23]

Japanese children born in Brazil were educated in schools founded by the Japanese community. Most simply learned to speak the Japanese linguistic communication and lived inside the Japanese community in rural areas. Over the years, many Japanese managed to buy their own state and became small farmers. They started to plant strawberries, tea and rice. Only 6% of children were the upshot of interracial relationships. Immigrants rarely accepted marriage with a not-Japanese person.[24]

By the 1930s, Brazilians complained that the independent Japanese communities had formed quistos raciais, or "racial cysts", and were unwilling to further integrate the Japanese Brazilians into Brazilian society.[21] The Japanese government, via the Japanese consulate in São Paulo, was direct involved with the instruction of Japanese children in Brazil. Japanese pedagogy in Brazil was modeled afterwards education systems in Japan, and schools in Japanese communities in Brazil received funding directly from the Japanese authorities.[21] Past 1933, there were 140,000-150,000 Japanese Brazilians, which was past far the largest Japanese population in any Latin American land.[25]

With Brazil under the leadership of Getúlio Vargas and the Empire of Nihon involved on the Centrality side in World War II, Japanese Brazilians became more isolated from their mother state. Japanese leaders and diplomats in Brazil left for Nihon after Brazil severed all relations with Japan on 29 January 1942, leading Japanese Brazilians to fend for themselves in an increasingly-hostile country. Vargas's regime instituted several measures that targeted the Japanese population in Brazil, including the loss of freedom to travel within Brazil, censorship of Japanese newspapers (fifty-fifty those printed in Portuguese), and imprisonment if Japanese Brazilians were caught speaking Japanese in public.[21] Japanese Brazilians became divided amongst themselves, and some fifty-fifty turned to performing terrorist acts on Japanese farmers who were employed by Brazilian farmers.[21] Past 1947, however, post-obit the end of World War 2, tensions between Brazilians and their Japanese population had cooled considerably. Japanese-linguistic communication newspapers returned to publication and Japanese-linguistic communication education was reinstituted amid the Japanese Brazilian population. World War 2 had left Japanese Brazilians isolated from their mother country, censored by the Brazilian government, and facing internal conflicts within their ain populations, but, for the nigh part, life returned to normal following the finish of the war.

Prejudice and forced assimilation [edit]

On 28 July 1921, representatives Andrade Bezerra and Cincinato Braga proposed a law whose Commodity 1 provided: "The clearing of individuals from the black race to Brazil is prohibited." On 22 October 1923, representative Fidélis Reis produced another neb on the entry of immigrants, whose 5th commodity was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian [immigrants] in that location will be immune each yr a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country. . . ."[26]

Some years before World War Ii, the regime of President Getúlio Vargas initiated a process of forced assimilation of people of immigrant origin in Brazil. The Constitution of 1934 had a legal provision about the subject: "The concentration of immigrants anywhere in the land is prohibited, the law should govern the selection, location and assimilation of the alien". The assimilationist projection affected mainly Japanese, Italian, Jewish, and High german immigrants and their descendants.[27]

In the regime's conception, the non-White population of Brazil should disappear within the dominant grade of Portuguese Brazilian origin.[ citation needed ] This way, the mixed-race population should be "whitened" through selective mixing, and so a preference for European immigration. In consequence, the non-white population would, gradually, accomplish a desirable White phenotype. The government focused on Italians, Jews, and Japanese.[ citation needed ] The formation of "ethnic cysts" among immigrants of non-Portuguese origin prevented the realization of the whitening projection of the Brazilian population. The government, and then, started to deed on these communities of foreign origin to force them to integrate into a "Brazilian culture" with Portuguese roots. It was the ascendant idea of a unification of all the inhabitants of Brazil nether a single "national spirit". During Earth War Two, Brazil severed relations with Nihon. Japanese newspapers and teaching the Japanese language in schools were banned, leaving Portuguese equally the simply choice for Japanese descendants. Newspapers in Italian or German were also advised to cease production, every bit Italia and Deutschland were Nippon's allies in the state of war.[17] In 1939, research of Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil, from São Paulo, showed that 87.seven% of Japanese Brazilians read newspapers in the Japanese language, a high figure for a land with many illiterate people like Brazil at the fourth dimension.[28]

The Japanese appeared every bit undesirable immigrants within the "whitening" and assimilationist policy of the Brazilian government.[28] Oliveira Viana, a Brazilian jurist, historian and sociologist described the Japanese immigrants every bit follows: "They (Japanese) are like sulfur: insoluble". The Brazilian mag "O Malho" in its edition of 5 December 1908 issued a charge of Japanese immigrants with the post-obit fable: "The government of São Paulo is stubborn. Afterwards the failure of the start Japanese immigration, it contracted 3,000 yellow people. It insists on giving Brazil a race diametrically reverse to ours".[28] In 1941, the Brazilian Government minister of Justice, Francisco Campos, dedicated the ban on admission of 400 Japanese immigrants in São Paulo and wrote: "their despicable standard of living is a barbarous competition with the country's worker; their selfishness, their bad faith, their refractory character, make them a huge indigenous and cultural cyst located in the richest regions of Brazil".[28]

The Japanese Brazilian community was strongly marked by restrictive measures when Brazil alleged war against Japan in August 1942. Japanese Brazilians could not travel the state without prophylactic conduct issued by the police; over 200 Japanese schools were airtight and radio equipment was seized to foreclose transmissions on short wave from Japan. The goods of Japanese companies were confiscated and several companies of Japanese origin had interventions, including the newly founded Banco América do Sul. Japanese Brazilians were prohibited from driving motor vehicles (fifty-fifty if they were taxi drivers), buses or trucks on their holding. The drivers employed by Japanese had to have permission from the police. Thousands of Japanese immigrants were arrested or expelled from Brazil on suspicion of espionage. There were many anonymous denunciations of "activities confronting national security" arising from disagreements between neighbours, recovery of debts and even fights between children.[28] Japanese Brazilians were arrested for "suspicious activity" when they were in artistic meetings or picnics. On 10 July 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese and German and Italian immigrants who lived in Santos had 24 hours to close their homes and businesses and move abroad from the Brazilian coast. The constabulary acted without whatsoever notice. About 90% of people displaced were Japanese. To reside in Baixada Santista, the Japanese had to have a safe acquit.[28] In 1942, the Japanese community who introduced the tillage of pepper in Tomé-Açu, in Pará, was virtually turned into a "concentration campsite". This time, the Brazilian administrator in Washington, D.C., Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, encouraged the government of Brazil to transfer all the Japanese Brazilians to "internment camps" without the demand for legal support, in the aforementioned manner as was done with the Japanese residents in the The states. No single suspicion of activities of Japanese against "national security" was confirmed.[28]

During the National Elective Assembly of 1946, the representative of Rio de Janeiro Miguel Couto Filho proposed Amendments to the Constitution every bit follows: "It is prohibited the entry of Japanese immigrants of any age and whatsoever origin in the country". In the last vote, a tie with 99 votes in favour and 99 against. Senator Fernando de Melo Viana, who chaired the session of the Constituent Assembly, had the casting vote and rejected the constitutional amendment. Past only one vote, the immigration of Japanese people to Brazil was non prohibited by the Brazilian Constitution of 1946.[28]

The Japanese immigrants appeared to the Brazilian regime as undesirable and non-assimilable immigrants. As Asian, they did not contribute to the "whitening" process of the Brazilian people as desired by the ruling Brazilian elite. In this process of forced assimilation the Japanese, more than any other immigrant group, suffered the ethno-cultural persecution imposed during this menstruation.[28]

Prestige [edit]

For decades, Japanese Brazilians were seen as a not-assimilable people. The immigrants were treated simply as a reserve of inexpensive labour that should be used on coffee plantations and that Brazil should avoid absorbing their cultural influences. This widespread conception that the Japanese were negative for Brazil was changed in the following decades. The Japanese were able to overcome the difficulties along the years and drastically ameliorate their lives through difficult work and pedagogy; this was also facilitated by the involvement of the Japanese authorities in the process of migration. The image of hard working agriculturists that came to help develop the country and agriculture helped erase the lack of trust of the local population and create a positive prototype of the Japanese. In the 1970s, Japan became i of the richest countries of the world, synonymous with modernity and progress. In the aforementioned catamenia, Japanese Brazilians achieved a great cultural and economic success, probably the immigrant group that nigh rapidly achieved progress in Brazil. Due to the powerful Japanese economy and due to the rapid enrichment of the Nisei, in the last decades Brazilians of Japanese descent achieved a social prestige in Brazil that largely contrasts with the assailment with which the early immigrants were treated in the state.[28] [29]

-

-

Japanese immigrants working on coffee plantation

-

Japanese immigrants working on coffee plantation

-

-

Japanese Immigrants on tea plantation in Registro, SP

-

Japanese immigrants with silkworm breeding

-

Japanese shop in São Paulo, SP

-

Fábio Riodi Yassuda, a Nisei who became the first Brazilian minister of Japanese descent.

Integration and intermarriage [edit]

| Intermarriage in the Japanese Brazilian community[24] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | Denomination in | Proportion of each generation in all community (%) | Proportion of mixed-race in each generation (%) | |

| Japanese | English language | |||

| 1st | Issei | Immigrants | 12.51% | 0% |

| second | Nisei | Children | xxx.85% | 6% |

| 3rd | Sansei | Grandchildren | 41.33% | 42% |

| quaternary | Yonsei | Great-grandchildren | 12.95% | 61% |

As of 2008, many Japanese Brazilians belong to the third generation (sansei), who make upwardly 41.33% of the community. First generation (issei) are 12.51%, 2d generation (nisei) are 30.85% and quaternary generation (yonsei) 12.95%.[24]

A more than recent phenomenon in Brazil is intermarriages between Japanese Brazilians and non-indigenous Japanese. Though people of Japanese descent brand up simply 0.8% of the country'due south population, they are the largest Japanese community outside Japan, with over 1.iv million people. In areas with large numbers of Japanese, such as São Paulo and Paraná, since the 1970s, large numbers of Japanese descendants started to marry into other indigenous groups. Jeffrey Lesser's work has shown the complexities of integration both during the Vargas era, and more recently during the dictatorship (1964–1984)

Present, among the i.4 million Brazilians of Japanese descent, 28% accept some non-Japanese ancestry.[thirty] This number reaches only 6% amidst children of Japanese immigrants, but 61% among great-grandchildren of Japanese immigrants.

Religion [edit]

Immigrants, every bit well as most Japanese, were mostly followers of Shinto and Buddhism. In the Japanese communities in Brazil, there was a strong effort by Brazilian priests to proselytize the Japanese. More recently, intermarriage with Catholics as well contributed to the growth of Catholicism in the community.[31] Currently, lx% of Japanese-Brazilians are Roman Catholics and 25% are adherents of a Japanese organized religion.[31]

Martial arts [edit]

The Japanese clearing to Brazil, in particular the clearing of the judoka Mitsuyo Maeda, resulted in the evolution of i of the most effective modernistic martial arts, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. Japanese immigrants likewise brought sumo wrestling to Brazil, with the offset tournament in the country organized in 1914.[32] The country has a growing number of amateur sumo wrestlers, with the just purpose-built sumo arena outside Japan located in São Paulo.[33] Brazil also produced (as of January 2022) sixteen professional person wrestlers, with the almost successful being Kaisei Ichirō.[34]

Language [edit]

The cognition of the Japanese and Portuguese languages reflects the integration of the Japanese in Brazil over several generations. Although first generation immigrants volition often not learn Portuguese well or not apply it often, nigh 2d generation are bilingual. The third generation, however, are virtually likely monolingual in Portuguese or speak, along with Portuguese, non-fluent Japanese.[35]

A study conducted in the Japanese Brazilian communities of Aliança and Fukuhaku, both in the country of São Paulo, released data on the linguistic communication spoken past these people. Before coming to Brazil, 12.2% of the first generation interviewed from Aliança reported they had studied the Portuguese language in Japan, and 26.eight% said to accept used information technology one time on arrival in Brazil. Many of the Japanese immigrants took classes of Portuguese and learned virtually the history of Brazil earlier migrating to the country. In Fukuhaku only 7.7% of the people reported they had studied Portuguese in Japan, but 38.5% said they had contact with Portuguese once on inflow in Brazil. All the immigrants reported they spoke exclusively Japanese at home in the first years in Brazil. Yet, in 2003, the figure dropped to 58.5% in Aliança and 33.three% in Fukuhaku. This probably reflects that through contact with the younger generations of the family, who speak mostly Portuguese, many immigrants also began to speak Portuguese at home.

The first Brazilian-born generation, the Nisei, alternate betwixt the use of Portuguese and Japanese. Regarding the employ of Japanese at domicile, 64.3% of Nisei informants from Aliança and 41.v% from Fukuhaku used Japanese when they were children. In comparing, only 14.3% of the tertiary generation, Sansei, reported to speak Japanese at dwelling when they were children. It reflects that the second generation was mostly educated by their Japanese parents using the Japanese language. On the other hand, the tertiary generation did not have much contact with their grandparent'south language, and virtually of them speak the national linguistic communication of Brazil, Portuguese, every bit their mother natural language.[36]

Japanese Brazilians usually speak Japanese more ofttimes when they live along with a kickoff generation relative. Those who do not live with a Japanese-born relative commonly speak Portuguese more than oftentimes.[37] Japanese spoken in Brazil is usually a mix of different Japanese dialects, since the Japanese community in Brazil came from all regions of Japan, influenced by the Portuguese language. The high numbers of Brazilian immigrants returning from Japan will probably produce more than Japanese speakers in Brazil.[24]

Distribution and population [edit]

| 2000 IBGE estimates for Japanese Brazilians[38] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Population of Japanese Brazilians | ||

| São Paulo | 693,495 | ||

| Paraná | 143,588 | ||

| Bahia | 78,449 | ||

| Minas Gerais | 75,449 | ||

| Others | 414,704 | ||

| Total | one,435,490 | ||

In 2008, IBGE published a book nigh the Japanese diaspora and it estimated that, equally of 2000 there were lxx,932 Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil (compared to the 158,087 plant in 1970). Of the Japanese, 51,445 lived in São Paulo.[38] : 37 About of the immigrants were over lx years old, considering the Japanese immigration to Brazil has ended since the mid-20th century.[39]

According to the IBGE, as of 2000, there were ane,435,490 people of Japanese descent in Brazil. The Japanese immigration was concentrated to São Paulo and, still in 2000, 48% of Japanese Brazilians lived in this state. There were 693,495 people of Japanese origin in São Paulo, followed by Paraná with 143,588. More recently, Brazilians of Japanese descent are making presence in places that used to accept a pocket-size population of this group. For example: in 1960, at that place were 532 Japanese Brazilians in Bahia, while in 2000 they were 78,449, or 0.6% of the state'south population.[38] Northern Brazil (excluding Pará) saw its Japanese population increase from 2,341 in 1960 (0.2% of the total population) to 54,161 (0.8%) in 2000. During the same period, in Central-Western Brazil they increased from 3,583 to 66,119 (0.vii% of the population).[38] [twoscore] Notwithstanding, the overall Japanese population in Brazil is shrinking, secondary to a decreased birth rate and an crumbling population; return immigration to Japan,[41] [42] [43] likewise as intermarriage with other races and dilution of indigenous identity.

For the whole Brazil, with over 1.4 million people of Japanese descent, the largest percentages were found in u.s. of São Paulo (1.ix% of Japanese descent), Paraná (1.v%) and Mato Grosso do Sul (ane.iv%). The smallest percentages were found in Roraima and Alagoas (with merely 8 Japanese). The percentage of Brazilians with Japanese roots largely increased among children and teenagers. In 1991, 0.vi% of Brazilians between 0 and 14 years old were of Japanese descent. In 2000, they were 4%, as a result of the returning of Dekasegis (Brazilians of Japanese descent who piece of work in Japan) to Brazil.[44]

Prototype gallery [edit]

-

Japanese in a Brazilian forest.

-

Japanese immigrants with their planting of potatoes.

-

Japanese family in Brazil.

-

Japanese family unit in Brazil.

-

Japanese on coffee plantation (1930).

-

The first immigrants on the Kasato Maru send (1908).

-

Japanese immigrants in Brazil.

-

Matrimony of Japanese immigrants at São Paulo land, Brazil.

-

Brazilian couple. Inter-racial couple in Brazil; unusual during the '60s in rural areas.

-

Japanese in São Paulo-Brazil, Liberdade neighbourhood, in a Shinto chapel.

-

Brazilian issei, (start generation of Japanese immigrant), reading paper in Romaji, while the shown championship is about Kardec spiritism (a French–Brazilian sect) which is quite similar to Shinto and Buddhist principles.

-

Grouping of Japanese descendants with Brazilians working resting afterward tree cut, to clear areas for coffee plantations in Brazil, '50s and '60s.

-

Brazilians, second generation subsequently Japanese immigration (sanseis) in rural areas, coffee plantations, São Paulo state, Brazil.

Japanese from Maringá [edit]

A 2008 demography revealed details about the population of Japanese origin from the metropolis of Maringá in Paraná, making it possible to have a contour of the Japanese-Brazilian population.[45]

- Numbers

At that place were 4,034 families of Japanese descent from Maringá, comprising 14,324 people.

- Dekasegi

ane,846 or xv% of Japanese Brazilians from Maringá were working in Nippon.

- Generations

Of the 12,478 people of Japanese origin living in Maringá, 6.61% were Issei (born in Nihon); 35.45% were Nisei (children of Japanese); 37.72% were Sansei (grandchildren) and xiii.79% were Yonsei (great-grandchildren).

- Boilerplate age

The boilerplate age was of 40.12 years former

- Gender

52% of Japanese Brazilians from the city were women.

- Average number of children per woman

2.4 children (similar to the average Southern Brazilian woman)

- Religion

Most were Roman Catholics (32% of Sansei, 27% of Nisei, x% of Yonsei and 2% of Issei). Protestant religions were the second virtually followed (half-dozen% of Nisei, 6% of Sansei, two% of Yonsei and i% of Issei) and next was Buddhism (v% of Nisei, 3% of Issei, 2% of Sansei and 1% of Yonsei).

- Family

49.66% were married.

- Knowledge of the Japanese linguistic communication

47% tin can sympathise, read and write in Japanese. 31% of the second generation and 16% of the third generation can speak Japanese.

- Schooling

31% simple pedagogy; thirty% secondary school and 30% higher education.

- Mixed-race

xx% were mixed-race (have some non-Japanese origin).

The Dekasegi [edit]

During the 1980s, the Japanese economic situation improved and achieved stability. Many Japanese Brazilians went to Nihon as contract workers due to economic and political problems in Brazil, and they were termed "Dekasegi". Working visas were offered to Brazilian Dekasegis in 1990, encouraging more than immigration from Brazil.

In 1990, the Japanese government authorized the legal entry of Japanese and their descendants until the third generation in Japan. At that time, Japan was receiving a large number of illegal immigrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, China, and Thailand. The legislation of 1990 was intended to select immigrants who entered Nippon, giving a clear preference for Japanese descendants from South America, specially Brazil. These people were lured to Nihon to work in areas that the Japanese refused (the so-called "iii K": Kitsui, Kitanai and Kiken – hard, dirty and unsafe). Many Japanese Brazilians began to emigrate. The influx of Japanese descendants from Brazil to Japan was and continues to be large: there are over 300,000 Brazilians living in Japan today, mainly as workers in factories.[46]

Because of their Japanese ancestry, the Japanese Government believed that Brazilians would be more than easily integrated into Japanese society. In fact, this easy integration did not happen, since Japanese Brazilians and their children born in Nihon are treated as foreigners by native Japanese.[47] [48] This apparent contradiction between existence and seeming causes conflicts of adaptation for the migrants and their acceptance by the natives.[49]

They also found the largest number of Portuguese speakers in Asia, greater than those of formerly Portuguese Due east Timor, Macau and Goa combined. Besides, Brazil, aslope the Japanese American population of the U.s., maintains its condition as home to the largest Japanese customs outside Japan.

Cities and prefectures with the about Brazilians in Japan are: Hamamatsu, Aichi, Shizuoka, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Gunma. Brazilians in Nippon are usually educated. However, they are employed in the Japanese automotive and electronics factories.[50] Most Brazilians go to Japan attracted past the recruiting agencies (legal or illegal) in conjunction with the factories. Many Brazilians are subjected to hours of exhausting work, earning a small salary past Japanese standards.[51] Withal, in 2002, Brazilians living in Nihon sent US$two.five billion to Brazil.[52]

Due to the fiscal crisis of 2007–2010, many Brazilians returned from Nippon to Brazil. From January 2011 to March, it is estimated that 20,000 Brazilian immigrants left Nippon.[53]

Brazilian identity in Nihon [edit]

In Japan, many Japanese Brazilians suffer prejudice because they practice non know how to speak Japanese fluently. Despite their Japanese appearance, Brazilians in Japan are culturally Brazilians, usually only speaking Portuguese, and are treated as foreigners.[54]

The children of Dekasegi Brazilians run into difficulties in Japanese schools.[55] Thousands of Brazilian children are out of school in Japan.[54]

The Brazilian influence in Japan is growing. Tokyo has the largest carnival parade outside of Brazil itself. Portuguese is the 3rd most spoken strange language in Japan, after Chinese and Korean, and is among the nigh studied languages past students in the country. In Oizumi, it is estimated that xv% of the population speak Portuguese equally their native linguistic communication. Japan has 2 newspapers in the Portuguese linguistic communication, besides radio and television stations spoken in that language. The Brazilian fashion and Bossa Nova music are also popular among Japanese.[56] In 2005, there were an estimated 302,000 Brazilian nationals in Japan, of whom 25,000 also hold Japanese citizenship.

100th ceremony [edit]

In 2008, many celebrations took place in Japan and Brazil to recollect the centenary of Japanese immigration.[57] Prince Naruhito of Japan arrived in Brazil on 17 June to participate in the celebrations. He visited Brasília, São Paulo, Paraná, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro. Throughout his stay in Brazil, the Prince was received by a crowd of Japanese immigrants and their descendants. He broke the protocol of the Japanese Monarchy, which prohibits physical contact with people, and greeted the Brazilian people. In the São Paulo sambódromo, the Prince spoke to 50,000 people and in Paraná to 75,000. He also visited the University of São Paulo, where people of Japanese descent brand up 14% of the 80,000 students.[58] Naruhito, the crown prince of Nippon, gave a speech in Portuguese.[59] [60]

Media [edit]

In São Paulo in that location are 2 Japanese publications, the São Paulo Shimbun and the Nikkey Shimbun. The former was established in 1946 and the latter was established in 1998. The latter has a Portuguese edition, the Jornal Nippak, and both publications have Portuguese websites. The Jornal Paulista, established in 1947, and the Diário Nippak, established in 1949, are the predecessors of the Nikkey Shimbun.[61]

The Nambei, published in 1916, was Brazil's first Japanese newspaper. In 1933 90% of East Asian-origin Brazilians read Japanese publications, including 20 periodicals, xv magazines, and five newspapers. The increment of the number of publications was due to Japanese immigration to Brazil. The government banned publication of Japanese newspapers during World War II.[61]

Tatiane Matheus of Estadão stated that in the pre-World State of war II catamenia the Nippak Shimbun, established in 1916; the Burajiru Jiho, established in 1917; and two newspapers established in 1932, the Japan Shimbun and the Seishu Shino, were the about influential Japanese newspapers. All were published in São Paulo.[61]

Education [edit]

Locations of Japanese international schools, 24-hour interval and supplementary, in Brazil recognized by MEXT (gray dots are for closed facilities)

Beneficência Nipo-Brasileira de São Paulo Edifice. The Association owns hospitals and social institutions across Brazil.[62]

Japanese international day schools in Brazil include the Escola Japonesa de São Paulo ("São Paulo Japanese School"),[63] the Associação Civil de Divulgação Cultural e Educacional Japonesa exercise Rio de Janeiro in the Cosme Velho neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro,[64] and the Escola Japonesa de Manaus.[65] The Escola Japonesa de Belo Horizonte (ベロ・オリゾンテ日本人学校),[66] and Japanese schools in Belém and Vitória previously existed; all three airtight, and their certifications by the Japanese education ministry building (MEXT) were revoked on March 29, 2002 (Heisei xiv).[67]

At that place are too supplementary schools teaching the Japanese linguistic communication and culture. As of 2003, in southern Brazil there are hundreds of Japanese supplementary schools. The Japan Foundation in São Paulo's coordinator of projects in 2003 stated that São Paulo State has about 500 supplementary schools. Around 33% of the Japanese supplementary schools in southeastern Brazil are in the urban center of São Paulo. Every bit of 2003 near all of the directors of the São Paulo schools were women.[68]

MEXT recognizes one part-time Japanese school (hoshu jugyo ko or hoshuko), the Escola Suplementar Japonesa Curitiba in Curitiba.[69] MEXT-approved hoshukos in Porto Alegre and Salvador have airtight.[70]

History of education [edit]

The Taisho School, Brazil'south first Japanese linguistic communication school, opened in 1915 in São Paulo.[71] In some areas full-time Japanese schools opened because no local schools existed in the vicinity of the Japanese settlements.[72] In 1932 over 10,000 Nikkei Brazilian children attended almost 200 Japanese supplementary schools in São Paulo.[73] By 1938 Brazil had a total of 600 Japanese schools.[72]

In 1970, 22,000 students, taught by 400 teachers, attended 350 supplementary Japanese schools. In 1992 there were 319 supplementary Japanese language schools in Brazil with a total of 18,782 students, 10,050 of them being female and eight,732 of them beingness male person. Of the schools, 111 were in São Paulo Country and 54 were in Paraná State. At the time, the São Paulo Metropolitan Area had 95 Japanese schools, and the schools in the urban center limits of São Paulo had six,916 students.[68]

In the 1980s, São Paulo Japanese supplementary schools were larger than those in other communities. In general, during that decade a Brazilian supplementary Japanese school had i or two teachers responsible for around 60 students.[68]

Hiromi Shibata, a PhD student at the Academy of São Paulo, wrote the dissertation As escolas japonesas paulistas (1915–1945), published in 1997. Jeff Bottom, author of Negotiating National Identity: Immigrants, Minorities, and the Struggle for Ethnicity in Brazil, wrote that the author "suggests" that the Japanese schools in São Paulo "were as much an affirmation of Nipo-Brazilian identity as they were of Japanese nationalism."[74]

Notable persons [edit]

Arts [edit]

- Erica Awano, artist and writer

- Roger Cruz, comic book creative person

- Fabio Ide, player and model

- Yuu Kamiya, manga artist and novelist

- Juliana Imai, model

- Adriana Lima, model

- Daniel Matsunaga, actor, and model

- Lovefoxxx (Luísa Hanae Matsushita), lead singer of CSS

- Carol Nakamura, model and actress

- Ruy Ohtake, architect

- Tomie Ohtake, artist

- Oscar Oiwa, artist

- Leandro Okabe, model

- Lisa Ono, vocaliser

- Ryot (Ricardo Tokumoto), cartoonist

- Akihiro Sato, actor and model

- Sabrina Sato, model and Television receiver host

- Daniele Suzuki, actress and Telly host

- Fernanda Takai, lead vocalizer of Pato Fu

- Carlos Toshiki (Carlos Toshiki Takahashi), singer-songwriter

- Luana Tanaka, extra

- Carlos Takeshi, histrion

- Marlon Teixeira, model

- Tizuka Yamasaki, film managing director

- Mateus Asato, Musician

Business [edit]

- Teruaki Yamagishi[75]

Politics [edit]

- Luiz Gushiken, sometime Minister of Communications

- Newton Ishii, Federal Law agent

- Kim Kataguiri, organizer of the Free Brazil Move[76]

- Juniti Saito, former commander of the Brazilian Air Force

Religious [edit]

- Júlio Endi Akamine, Roman Cosmic Archbishop

- Hidekazu Takayama, Assemblies of God pastor and politician

Sports [edit]

- Deco, footballer, represents Portugal internationally

- Sérgio Echigo, sometime footballer

- Sandro Hiroshi, former footballer

- Wagner Lopes, former footballer

- Ruy Ramos, onetime footballer

- Hugo Hoyama, table tennis player

- Vânia Ishii, judo wrestler

- Caio Japa, futsal histrion

- Kaisei Ichiro, sumo wrestler

- Stefannie Arissa Koyama, judoka

- Pedro Ken, footballer

- Bruna Leal, 2012 London Olympics gymnast

- Lyoto Machida, mixed martial arts fighter, karateka, erstwhile sumo wrestler and the former Ultimate Fighting Title light-heavyweight champion

- Chinzo Machida, mixed martial arts fighter, karateka, Bellator Fighter, 12 time Brazilian Karate Champion

- Mario Yamasaki, mixed martial arts referee, jiu-jitsu practitioner[77]

- Shigueto Yamasaki, judoka at 1992 Olympics[77]

- Goiti Yamauchi, mixed martial arts fighter, Bellator Fighter

- Scott MacKenzie, darts actor

- Mitsuyo Maeda, judo wrestler

- Arthur Mariano, 2016 Rio Olympics gymnast

- Andrews Nakahara, mixed martial arts fighter and karateka

- Paulo Miyao, Brazilian jiu-jitsu competitor

- Paulo Miyashiro, triathlete

- Paulo Nagamura, footballer

- Mariana Ohata, triathlete

- Tetsuo Okamoto, sometime swimmer

- Poliana Okimoto, long-altitude swimmer

- Noguchi Pinto, footballer

- Rogério Romero, old swimmer

- Lucas Salatta, swimmer

- Sérgio Sasaki, Rio 2016 Olympic Gymnast

- Manabu Suzuki, former racing commuter turned car magazine author and motorsport journalist

- Rafael Suzuki, racing driver

- Rodrigo Tabata, footballer, represents Qatar internationally

- Marcus Tulio Tanaka, footballer, represents Nippon internationally

- Bruna Takahashi, Table Tennis histrion

- Augusto Sakai, mixed martial arts fighter

- Daniel Japonês, futsal player

Meet also [edit]

- South America Hongwanji Mission

- List of Japanese Brazilians

- Asian Latin Americans

- Brazilians in Japan

- Brazil–Japan relations

- Japanese Peruvians

- Japanese Argentines

- Shindo Renmei

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Nippon-Brazil Relations". Ministry of Strange Affairs of Japan. November 26, 2019. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

Number of Japanese nationals residing in Brazil: 50,205 (2018); Number of Japanese descendants: 2 million (estimated)

- ^ "ブラジル連邦共和国(Federative Republic of Brazil)基礎データ|外務省". 外務省 (in Japanese). June 9, 2021. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Adital – Brasileiros no Japão Archived July 13, 2006, at the Wayback Car

- ^ "Brazil". country.gov. September xiv, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Gonzalez, David (September 25, 2013). "Japanese-Brazilians: Straddling Two Cultures". Lens Blog. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ Nakamura, Akemi (January fifteen, 2008). "Japan, Brazil marking a century of settlement, family ties". The Nippon Times Online. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Takeyuki Tsuda. "Strangers in the Ethnic Homeland – Japanese Brazilian Render Migration in Transnational Perspective". Columbia Academy Press. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ Jillian Kestler-D'Amours (June 17, 2014). "Japanese Brazilians celebrate mixed heritage". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ dos Santos, Sales Augusto (Jan 2002). "Historical Roots of the 'Whitening' of Brazil". Latin American Perspectives. 29 (ane): 61–82. doi:10.1177/0094582X0202900104. JSTOR 3185072.

- ^ Brasil 500 anos Archived May xxx, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "HISTÓRICA - Revista Eletrônica do Arquivo practice Estado". www.historica.arquivoestado.sp.gov.br. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Mosley, Leonard (1966). Hirohito, Emperor of Japan. London: Prentice Hall International, Inc. pp. 97–98.

- ^ Imigração Japonesa no Brasil Archived December xviii, 2007, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Barone, Michael (2013). Shaping Our Nation: How Surges of Migration Transformed America and Its Politics. Crown Forum. ISBN9780307461513.

- ^ "A little corner of Brazil that is forever Okinawa", BBC News, February 4, 2018, archived from the original on February 5, 2018

- ^ Osada, Masako. (2002). Sanctions and Honorary Whites: Diplomatic Policies and Economical Realities in Relations Between Japan and Due south Africa, p. 33.

- ^ a b Itu.com.br. "A Imigração Japonesa em Itu - Itu.com.br". itu.com.br. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved May four, 2018.

- ^ a b "Governo do Estado de São Paulo". Governo practice Estado de São Paulo. Archived from the original on Dec 31, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia eastward Estatística Archived October xiii, 1996, at the Portuguese Web Annal (visitado 4 de setembro de 2008)

- ^ 日系移民データ – 在日ブラジル商業会議所 – CCBJ Archived June 5, 2012, at the Wayback Car, which cites: "1941年までの数字は外務省領事移住部 『我が国民の海外発展-移住百年のあゆみ(資料集)』【東京、1971年】p140参照。 1952年から1993年の数字は国際協力事業団『海外移住統計(昭和27年度~平成5年度)』【東京、1994年】p28,29参照。"

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nishida, Mieko (2018). Diaspora and Identity: Japanese Brazilians in Brazil and Nihon. Honolulu: Academy of Hawai'i Printing. pp. 25–28. ISBN9780824874292.

- ^ Uma reconstrução da memória da imigração japones ano Brasil Archived May x, 2013, at the Wayback Car

- ^ An all-encompassing quotation from this article appears in Minas Geraes-class battleship.

- ^ a b c d Enciclopédia das Línguas no Brasil – Japonês Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (Accessed September four, 2008)

- ^ Normano, J. F. (March 1934). "Japanese Emigration to Brazil". Pacific Affairs. seven (i): 45. doi:10.2307/2750689. JSTOR 2750689 – via JSTOR.

- ^ RIOS, Roger Raupp. Text excerpted from a judicial sentence concerning criminal offense of racism. Federal Justice of 10ª Vara da Circunscrição Judiciária de Porto Alegre, November 16, 2001 [ permanent dead link ] (Accessed September 10, 2008)

- ^ Memória da Imigração Japonesa Archived May 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i j SUZUKI Jr, Matinas. História da discriminação brasileira contra os japoneses sai practice limbo in Folha de S.Paulo, 20 de abril de 2008 Archived Oct fifteen, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (visitado em 17 de agosto de 2008)

- ^ Darcy Ribeiro. O Povo Brasileiro, Vol. 07, 1997 (1997), pp. 401.

- ^ Hiramatsu, Daniel Afonso; Franco, Laércio Joel; Tomita, Nilce Emy (November 2006). "Influência da aculturação na autopercepção dos idosos quanto à saúde bucal em uma população de origem japonesa" [Influence of acculturation on self-perceived oral health among Japanese-Brazilian elderly]. Cadernos de Saúde Pública (in Portuguese). 22 (11): 2441–2448. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2006001100018. PMID 17091181.

- ^ a b "PANIB – Pastoral Nipo Brasileira". Archived from the original on June 29, 2008.

- ^ Benson, Todd (January 27, 2005). "Brazil's Japanese Preserve Sumo and Share Information technology With Others". The New York Times . Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Kwok, Matt (August 2, 2016). "'Sumo feminino': How Brazil's female sumo wrestlers are knocking downwardly gender barriers". CBC News . Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Find Rikishi - Brazil Shusshin". Sumo Reference . Retrieved January xiii, 2022.

- ^ Birello, Verônica Braga; Lessa, Patrícia (December 31, 2008). "A Imigração Japonesa do Passado e a Imigração Inversa, Questão Gênero east Gerações Na Economia" [The Japanese Immigration From the Past and the Inverse Immigration, Gender and Generations Issues in the Economic system of Brazil and Japan]. Defined@! (in Portuguese). 1 (1). doi:10.5380/diver.v1i1.34039.

- ^ Ota, Junko; Gardenal, Luiz Maximiliano Santin (2006). "As línguas japonesa e portuguesa em duas comunidades nipo-brasileiras: a relação entre os domínios east as gerações" [The Japanese and Portuguese languages in two Japanese-Brazilian communities: the relationship between domains and generations]. Lingüísticos (in Portuguese). 35: 1062–1071.

- ^ Doi, Elza Taeko (2006). "O ensino de japonês no Brasil como língua de imigração" [Japanese pedagogy in Brazil equally an immigration language]. Estudos Lingüísticos (in Portuguese). 35: 66–75.

- ^ a b c d Resistência & integração : 100 anos de imigração japonesa no Brasil (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Establish of Geography and Statistics. 2008. p. 71. ISBN978-85-240-4014-half dozen. Archived from the original on March three, 2021.

- p59 Tabela 1 has errors:

- Total for year 2000 (i,405,685) is wrong, missing data for Mato Grosso do Sul. p71 Apêndice two Total 1,435,490 is correct.

- População nikkey for yr 1991 are all wrong, mistakingly duplcating numbers from População total.

- straight link to pdf [1]

- p59 Tabela 1 has errors:

- ^ Japoneses IBGE Archived February nineteen, 2009, at the Wayback Car

- ^ www.zeroum.com.br, ZeroUm Digital -. "Centenário da Imigração Japonesa - Reportagens - Nipo-brasileiros estão mais presentes no Norte e no Centro-Oeste do Brasil". www.japao100.com.br. Archived from the original on Baronial thirteen, 2017. Retrieved May four, 2018.

- Centro-Oeste (5) 1960 and Total 2000 conflict with IBGE 2008 p71.

- ^ Naoto Higuchi (February 27, 2006). "BRAZILIAN MIGRATION TO Nippon TRENDS, MODALITIES AND IMPACT" (PDF). Un. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ Richard Gunde (Jan 27, 2004). "Japanese Brazilian Render Migration and the Making of Japan's Newest Immigrant Minority". 2013. The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ Higuchi, Naoto; Tanno, Kiyoto (Nov 2003). "What'southward Driving Brazil-Japan Migration? The Making and Remaking of the Brazilian Niche in Japan". International Journal of Japanese Sociology. 12 (i): 33–47. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6781.2003.00041.x.

- ^ "IBGE traça perfil dos imigrantes" [IBGE does a contour of immigrants] (in Portuguese). madeinjapan.uol.com.br. June 21, 2008. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008.

- ^ [ Japoneses e descendentes em Maringá passam de xiv mil "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)] - ^ "asahi.com : EDITORIAL: Brazilian immigration - English language". May 6, 2008. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved May four, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Sugimoto, Luiz (June 2002). "Parece, mas não é" [It seems, but it is not]. Jornal da Unicamp (in Portuguese).

- ^ Lara, Carlos Vogt, Mônica Macedo, Anna Paula Sotero, Bruno Buys, Rafael Evangelista, Marianne Frederick, Marta Kanashiro, Marcelo Knobel, Roberto Belisário, Ulisses Capozoli, Sérgio Varella Conceicao, Marilissa Mota, Rodrigo Cunha, Germana Barata, Beatriz Vocaliser, Flávia Tonin, Daisy Silva de. "Brasil: migrações internacionais e identidade". www.comciencia.br. Archived from the original on Baronial xix, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Beltrão, Kaizô Iwakami; Sugahara, Sonoe (June 2006). "Permanentemente temporário: dekasseguis brasileiros no Japão". Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População. 23 (1). doi:10.1590/S0102-30982006000100005.

- ^ "Estadao.com.br :: Especiais :: Imigração Japonesa". www.estadao.com.br. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "Folha Online - BBC - Lula ouve de brasileiros queixas sobre vida no Japão - 28/05/2005". www1.folha.uol.com.br . Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Untitled Document Archived September 12, 2012, at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ Brasileiros que trabalharam no Japão estão retornando ao Brasil Archived October 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Onishi, Norimitsu. "An Enclave of Brazilians Is Testing Insular Nihon," Archived February 2, 2017, at the Wayback Automobile New York Times. November 1, 2008.

- ^ Tabuchi, Hiroko. "Despite Shortage, Japan Keeps a High Wall for Foreign Labor," New York Times. January 3, 2011; extract, "...the authorities did little to integrate its migrant populations. Children of foreigners are exempt from compulsory education, for example, while local schools that accept non-Japanese-speaking children receive almost no aid in caring for their needs."

- ^ http://www.dothnews.com.br. "Japão: imigrantes brasileiros popularizam língua portuguesa". correiodoestado.com.br. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "Site Oficial da ACCIJB - Centenário da Imigração Japonesa no Brasil - Comemorações". world wide web.centenario2008.org.br. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ DISCURSO DA PROFA. DRA. SUELY VILELA NA VISITA OFICIAL DE SUA ALTEZA PRÍNCIPE NARUHITO, DO JAPÃO – FACULDADE DE DIREITO – June 20, 2008 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2008. Retrieved Oct 23, 2008.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Kumasaka, Alyne. "Site Oficial da ACCIJB - Centenário da Imigração Japonesa no Brasil - Festividade no Sambódromo emociona público". world wide web.centenario2008.org.br. Archived from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Após visita, príncipe Naruhito deixa o Brasil

- ^ a b c Matheus, Tatiane. "O outro lado da notícia Archived March 17, 2014, at the Wayback Motorcar." Estadão. February ix, 2008. Retrieved on March 17, 2014. "O primeiro jornal japonês no País foi o Nambei,[...]"

- ^ DIGITAL, DIN. "Enkyo - Beneficência Nipo-Brasileira de São Paulo". ENKYO. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Home page Archived March 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Escola Japonesa de São Paulo. Retrieved on March 18, 2014. "Estrada do Campo Limpo,1501, São Paulo-SP"

- ^ "学校紹介 Archived January 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine." Associação Civil de Divulgação Cultural eastward Educacional Japonesa do Rio de Janeiro. Retrieved on March 18, 2014. "Rua Cosme Velho,1166, Cosme Velho RIO DE JANEIRO,R.J,BRASIL,CEP22241-091"

- ^ Home page Archived May 6, 2015, at Wikiwix. Escola Japonesa de Manaus. Retrieved on March 18, 2014. "Caixa Postal 2261 Agencia Andre Araujo Manaus AM. Brasil CEP69065-970"

- ^ Home page Archived May 7, 2015, at the Wayback Auto. Escola Japonesa de Belo Horizonte. Retrieved on Jan 15, 2015.

- ^ "過去に指定・認定していた在外教育施設" (Archive). Ministry building of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Retrieved on Jan xv, 2015.

- ^ a b c Carvalho, Daniela de. Migrants and Identity in Japan and Brazil: The Nikkeijin. Routledge, August 27, 2003. ISBN 1135787654, 9781135787653. Page number unstated (Google Books PT46).

- ^ "中南米の補習授業校一覧(平成25年4月15日現在)" (Archive). Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Engineering science (MEXT). Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ "中南米の補習授業校一覧." MEXT. October 29, 2000. Retrieved on January 11, 2017. "ポルト・アレグレ 休 校 中 サルバドール 休 校 中 " (states the Porto Alegre and Salvador schools closed)

- ^ Goto, Junichi (Kyoto University). Latin Americans of Japanese Origin (Nikkeijin) Working in Japan: A Survey. World Bank Publications, 2007. p. 7-8.

- ^ a b Laughton-Kuragasaki, Ayami, VDM Publishing, 2008. p. x. "The immigrants opened Japanese schools for their children every bit they were living in the rural areas where there were no local schools for their children and no support from the local government. About 600 Japanese schools were open past 1938. The children were full-time students,[...]"

- ^ Goto, Junichi (Kyoto Academy). Latin Americans of Japanese Origin (Nikkeijin) Working in Japan: A Survey. Globe Bank Publications, 2007. p. 8.

- ^ Lesser, Jeff. Negotiating National Identity: Immigrants, Minorities, and the Struggle for Ethnicity in Brazil. Knuckles University Printing, 1999. ISBN 0822322927, 9780822322924. p. 231.

- ^ Ordem do Sol Nascente (Dec 16, 2008). "Yamagishi honored by Japan". yamagishi.com.br. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "Encounter the Teen Spearheading Brazil's Protests Against its President". Time. Oct 27, 2015. Archived from the original on December one, 2015.

- ^ a b Tatame Magazine >> Mario Masaki Interview Archived November 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. URL accessed on Oct xvi, 2010.

References [edit]

- Masterson, Daniel One thousand. and Sayaka Funada-Classen. (2004), The Japanese in Latin America: The Asian American Experience. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07144-7; OCLC 253466232

- Jeffrey Bottom, A Discontented Diaspora: Japanese-Brazilians and the Meanings of Ethnic Militancy, 1960–1980 (Durham: Knuckles University Press, 2007); Portuguese edition: Uma Diáspora Descontente: Bone Nipo-Brasileiros e os Significados da Militância Étnica, 1960–1980 (São Paulo: Editora Paz e Terra, 2008).

- Jeffrey Bottom, Negotiating National Identity: Immigrants, Minorities and the Struggle for Ethnicity in Brazil (Durham: Duke Academy Press, 1999); Portuguese edition: Negociando an Identidade Nacional: Imigrantes, Minorias e a Luta pela Etnicidade no Brasil (São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2001).

Further reading [edit]

- Shibata, Hiromi. As escolas Japonesas paulistas (1915–1945) (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Sao Paulo, 1997).

- Sasaki, Elisa (Baronial 2006). "A imigração para o Japão". Estudos Avançados. xx (57): 99–117. doi:x.1590/S0103-40142006000200009.

External links [edit]

- Sociedade Brasileira de Cultura Japonesa

- Fundação Japão em São Paulo

- Centenário da Imigração Japonesa no Brasil (1908–2008)

- Tratado de Amizade Brasil-Japão

- Tratado de Migração due east Colonização Brasil-Japão

- Site da Imigração Japonesa no Brasil

- Leia sobre os navios de imigrantes que aportaram no Porto de Santos

- Site comemorativo do Centenário da Imigração Japonesa que coleta histórias de vida de imigrantes e descendentes

- Eye for Japanese-Brazilian Studies (Centro de Estudos Nipo-Brasileiros)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_Brazilians

Postar um comentário for "Perfumeria Brasil Is Owned by Japanese Brazilian Family"